Theater is the most ephemeral of all arts, and, at the same time, it also has the greatest capacity to entertain. Stanislavski meditates in My Life In Art on this combination of qualities as the reason for the lack of aesthetic development of the theater when compared to other media (like literature, music, painting and sculpture, all of which had been turned on their ears repeatedly when Stanislavski was working). It is simply too easy for artists in the theater to get by by entertaining their audiences, or, to put a finer point on it, it is too hard for them not to. An audience walks into a theater expecting a less formally aesthetic experience. Theater exists in time, as life does, and is gone in a moment, just as events in life are. Acting exists in the minds of much of the audience as entertaining diversion and realistic imitation, thanks to television and film—where other arts are more clearly (and obviously) formal and at times abstractly imitative. And, until recently, audiences would only pay for theater that gave them exactly what they expected.

James Tyrone (played in the Gift's production by Gary Wingert, whose face seems the archetypal aging Irish actor), the central character of Long Day's Journey Into Night, is an ephemeral man. He worked his way up from desperate poverty to prominence as an actor. As he ages, he is living with the regret that he sacrificed any chance of serious artistic work (for him, this means attaining status as a “great” Shakespearean) for financial security. Security is his chief concern in life—to live on a solid foundation, so that he never runs the risk of returning to the poverty in which he was raised. To that end, he endlessly sinks his money, over the objections of his family, into land investments. His summer home, in which the play is set, is bathed in fog, and a foghorn keeps his addled wife up at night, a fact to which he is brutally senseless. He lives in a self-induced haze of delusion and alcohol, and he cannot allow himself to see the solid truth about himself or his family.

The play is itself largely about Tyrone and the other members of his family (who are to varying degrees living in the same haze that envelops James) forcing themselves and one another to run aground upon the realities that they deny to get by. It is a metaphysical piece, in which the forces of time and nature themselves are allegorically illustrative of the story. As the forces of nature conspire to run these tortured characters aground on the rocks of their delusions, we see them sink themselves deeper into addiction and recrimination.

At the risk of being labeled a complete lackey of Robert Brustein, I quote him again, this time in his review of The Iceman Cometh: “the length of the play contributes to its impact, as if we had to be exposed to virtually every aspect of universal suffering in order to feel its full force.” I would actually go further: because O'Neill wrote such metaphysical work, I believe that his style (the long, dense interior drama) is actually meant create a different theatrical context in which the audience experiences things in time. It is meant to use time to make the audience sense, in their bodies (through the natural change that physically occurs in several hours) the passage of time, and to link that physical sense of the passage of time to characters—in order to elevate those characters to the level of archetypes. We make emotional realizations, in time, and this elevates these emotions to a different context from others we experience in drama. It is as such that he has created such a lasting impact on American theater.

However, therein lies a dilemma, in addition to the inherent dilemmas of making theater. If O'Neill's (novelistic in scope) work is set close to or at real time, how should it be presented? Should we stage it realistically (or as O'Neill himself said “holding the old family Kodak up to ill-nature)? Should we present it in real time, at the risk of alienating our audience?

Fortunately, O'Neill is a master storyteller, who is constantly supplying his audiences with fresh and interesting events, actions, and conflicts, all the while endowing his audience with a sea of facts from which they can make very rich inferences about the world of characters in the play and the emotional stakes for those characters. All the same, an O'Neill play is not for the faint of heart, or for that matter, of backside. Audiences should know what they're getting going in.

The Gift has chosen to stage the piece in a very realistic, well-constructed, setting. The Tyrone summer home is a spartan, wooden building, complete with shutters at the top of the walls, with manly swords and busts and paintings of Shakespeare and Booth, woven rug, wood floor, and dirty windows. It is lit warmly, in the morning of the first act, through slots between the wooden wall panels, creating a very nice effect.

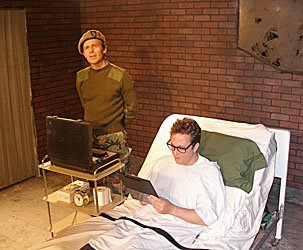

The first two acts are scored at a very fast pace, as we see the family men's attempt to insulate Mary Tyrone, the mother of the family (Alexandra Main, cast as a woman easily 20 years her senior), from the strife that consumes them. She has recently returned (we discover later from a cheap clinic, being treated for morphine addiction) and everyone wants to protect her. This quickly disintegrates as James accuses his sons of laziness, drunkenness, lechery, and leeching. Jamie (John Kelly Connolly), the eldest son, is quick to respond with accusations of James' cheapness and cruelty, while Edmund (Brendan Donaldson), the effete and sickly youngest son, tries to stay clear of the punches. The characters in this play, in addition to doing yard work, visiting doctors, eating, and napping are constantly trying to define the past in conversation to blame each other for the misery in which they find themselves.

The play follows a pattern of accusation, recrimination, repentance, incomplete forgiveness and incomplete peace, followed shortly thereafter by more accusations. In this production, the events in the first two acts, as O'Neill is informing us about the world into which we have entered, are not well articulated. Some of the most horrible accusations and recriminations pass without the tempo of the piece altering. The events are not well bracketed. Perhaps this is meant to emphasize the hazy banality of the fighting. Perhaps this is to emphasize the dynamism of the fourth act, in which the key event, of Edmund's accusation of his father of willful neglect runs him aground on reality. In any event, the acting was fast, and I was unable to discern what director Michael Patrick Thornton conceived to be events in the flurry of the information rushing at me.

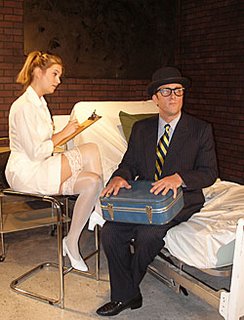

The third act opens to the family's temporary servant, fresh Irish immigrant Catherine (Sue Redmond, using an excellent brogue) and Mary chatting in the aftermath of another of Mary's relapses into morphine abuse. Catherine is getting drunk on James' whiskey, and lapping it up, at Mary's urging. Mary needs the company, as she is all alone, in a house she despises, without any roots surrounding her or companionship. Catherine's energy in this production alters the stasis of tone achieved by the family's fighting in the first two acts, and is also an interesting quiet counterpoint to Mary's cascade of illusions about her own childhood and the source of her addiction. O'Neill is charitable to Mary, exposing her to the moral indictment to which all other characters in this piece are subjected, but chiefly using Catherine's charming skepticism to call the bullshit. The tempo of the piece is dramatically altered here. And when Edmund returns from the doctor's office with news that he indeed has consumption (TB) and will have to be hospitalized, his confrontation with Mary is very evocative.

The fourth act, however, is made to stand out in this production. I suspect it is presented in boldface because in it, we are presented with accusations and admissions that happen once in a lifetime and alter the lives of the characters forever. It is, in this production, the only act in which major events transpire. It is intense, dynamic, and built around Edmund's accusation that his father is willfully neglecting him, possibly to death, in the treatment of his consumption. The men are all drunk, and their drunkenness gives them real license to say what needs to be said. James paints the bleak picture of his childhood that Edmund is accustomed to hearing, but he then admits that his stinginess and fear of the poor house led him to destroy his artistic potential, by allowing himself to be typecast lucratively. This is another key event, as we experience the pathos of regret with the hypocritical, cheap, cruel father. Jamie returns and drunkenly confesses his secret wish to destroy his brother, as well as his love for his brother. The play ends with Mary's recounting of a story in which she was rejected from the convent, to test her religious devotion in the secular world, and with a tunnel of light on Edmund, as the fulcrum upon which the family has now shifted.

The lighting in the piece (Heather Gilbert) is fairly straightforward, with Thornton using a special to create a tunnel of light on Mary at various moments in her downturn. The lighting suggests, very subtlely, shifts in mood in the third and fourth act, and the darkness that envelops the house as the day wears down. The costumes (Kimberly G. Morris) evoke the period well, and James' rubber-band billfold is one of many nice touches (another is the collection of Kipling's poems that were aptly a part of James' library). I found myself straining to hear over the air conditioner at various points in the piece, a price one pays at storefront theaters. The changes in scenes were marked by Brahms-esque piano sonatas, Vivaldi's Four Seasons, and the show closes to Pachelbel's Cannon. (Sound was co-designed by Bob Mihlfried, Jr. with his brother Kenny, who also composed the original music). In the third and fourth acts we get some very nice atmospheric sound—of crickets and of the water and sea bells in the distance.

The script is so rich in themes: it explores the American need to establish and maintain oneself individually. It is also an examination of the animating hypocrisy of those caught in addiction—who obsess over moderation and willpower, but whose obsession in that regard is indicative of their deep fixation on those qualities as inadequacies. But it is, chiefly, a metaphysical work, aided by the brothers' fixation on post-enlightenment writers and literature. By the art they admire and strive to create, they are wresting the future of American culture from those like James, who has spent his life groping for solidity in the mists of uncertainty. They are more comfortable with a future without absolutes, and the art and culture of the past fifty years has borne out O'Neill's view of the world changing. Of course, the enduring power of the story is that is is generational in nature—with the old reaching for certainty as they face mortality, and the young embracing it.

The work in the fourth act was so powerful that I was left speechless. A question nagged at me, however, as I drove home from Jefferson Park (in addition to questioning the casting of such a young woman as Mary, opposite such a powerful older actor like Wingert): Why? Why was this play staged, now? The Gift Theater has a wonderful reputation as an acting repertory, and many of the scenes in this play are meaty enough for a tight ensemble and director to display their acting chops (to mix metaphors). Of course, any time an actor ascends the stage his embodiment is itself a representation living in the present time—as such the actor’s interpretation is itself, upon close examination, a commentary on the here and now. And of course, O’Neill’s play itself is rich enough that one can find apt metaphors pertaining to the current degeneration of society under vice and the attendant recriminations (amongst others) to one’s interpretive heart’s delight. But these interpretations are at their heart general, and based upon abstractions, and not the basis for any firm statement in a dialogue between the artist and his culture.

Indeed, there is little to no suggestion provided by Thornton’s production about why O’Neill’s work is relevant today. The production could have fixated on any of the relevant themes in the script as a focus for engaging contemporary issues. However, I could very easily see the same production having been staged in the mid-nineties, or at any time in the past forty years. There is something to be said for a “light touch” in the creation of art theater, and for providing a venue in which the actor’s art can by itself provide commentary enough on society—and this is what the Gift achieves, for better or worse. Directors of Shakespeare’s plays are constantly working to expand their productions’ cultural context—I wonder if it is possible for a director working with O’Neill’s behemoth literary masterpiece to do the same.

The fourth act was diverting, but it was the apex of a show whose power was more or less as an actor's piece—and relatively ephemeral. O'Neill's literature is itself rich enough to create atmosphere without the construction of a period set to make it tangible. I wonder if a staging that would have embraced the key metaphysical uncertainties which compose the play's obsessions would have been more effective than one that strives to reach for an elusive sense of security. What I mean to suggest is that a realistic staging may actually render the piece less effective than one that suggests a critical context in which the piece should be viewed as social or cosmic commentary.

James Tyrone's regret is that his legacy is totally ephemeral. A realistic staging may be clear, comfortable, and reassuring to unsteady audiences, but if this play is staged only as an actor's piece, then its power is itself ephemeral, and its tragedy is the same as James Tyrone's—that in striving for security, it eradicates any chance for a lasting impact and legacy.