Proving Mr. Jennings is based on an interesting conceit. Take a rather self-righteous, pompous, white urban professional liberal lawyer and place him in a succession of predicaments identical to those endured by many enemy combatants and captives taken under shadowy pretenses in the Global War on Terror (GWOT). Then, explode his guts all over the inside of the theater.

While George Cederquist is a gutsy director, he isn't that gutsy. He is satisfied to close the show with the sound of an intense interior bomb blast. It is an effective move because the rest of the play is defined by an atmosphere that can best be described as “Disney Symphonic.” As the audience enters the spare Actors Workshop Theatre to take in this story of torture, denial of due process, and startling humiliation, it is to sounds that are reminicient of naughty cartoon characters engaged in wacky hijincks on Saturday morning.

This, I expect, is Cederquist's response to the challenge of staging a play that takes on such a serious contemporary subject. James Walker, with whom Cederquist went to high school, has written a stinging political satire in the style of Christopher Durang. Like Durang, he uses the convention of storytelling to discover effective metaphors for the ridiculous in our culture, and constantly raises the stakes in terms of the ridiculousness. When the audience is confronted with the on stage torture of a main character who looks and (judging by the conversations overheard by this intrepid reviewer) thinks like them, the production could shock them with the veracity of what transpires, or it can use a Brechtian “wink” to signify that the events are slightly exaggerated for instructional purposes. This does more than save us from discomfort. It highlights the distinction between our treatment of western and foreign, brown-skinned lives. We know that what Walker highlights is happening to others in some form—and yet our response to the thought of someone like us enduring that type of treatment is powerful, and completely distinct from our response to what we see in the news. We are able to think about, rather than respond to, what we see. While I feel that Durang's satire is more indirect than Walker's, the parallels are certainly there.

Brustein (in his essay on Rum and Coke in Who Needs Theatre) cites a Philip Roth quote about the impossibility of writing social satire due to the extremity of Americans' actions in the late 20th century. The key in plays that strive to satirize the inherently ridiculous, Brustein points out, is tone, and this play, and the tone established by Cederquist manages to satrize not only the government's absurd actions, but our response to the government's actions during the past five years.

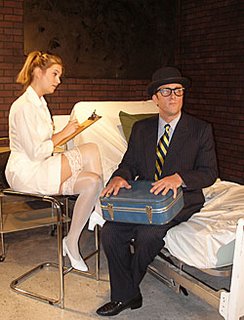

Jennings (Damien Arnold), singing to himself, has checked into an apparently “excellent” National Heath Service (he's English) clinic for a life-saving heart transplant. It's clear that Walker has written this from the beginning unrealistically—the transplant is treated like a severly ingrown toe nail—somewhat life-threatening, but nothing to be too worked up about. The nurse (Julie Griffith) enters to perform a series of ridiculous tests, but mostly tries to seduce Jennings. The unreality of the atmosphere has the audience considering the symbolic relevance of a pinstriped Englishman blithely refusing sex with a beautiful woman and being given a new heart. The point is clear—Jennings isn't just English, and doesn't just have a deficient heart—he has a deficient heart, and he's cold, even for an Englishman.

He's fastidious about the red spots on his hospital gown—he's fastidious about everything. As he changes, we see his socks with stirrups. He recognizes the slutty nurse as a woman he once prosecuted for engaging in certain “fashionable sexual offenses.” This adds to his chagrin at the conditions of his treatment.

He's then questioned as to medical history, and then, suddenly, about subversive activities—including membership in subversive societies. He admits to only one, his local cricket club.

He takes a tablet that puts him to sleep in the large hospital bed that occupies the center of the small stage. Cederquist has chosen to stage the piece on a shallow procenium—the audience sits in two-thirds of the shoebox, and the action of the play takes place in the other third. The scene change is marked by more Disney music, a ticking clock, lowered lights (one of a few variations in lighting in what seemed a simple light design), and other cast members pulling down the green hospital gown walls to reveal brick underground and a pane of one-way glass. The bed is rearranged.

The doctor (Don Swanson) walks in and revives Jennings with a shot. Jennings has had an awful dream, which he describes. In a comic turn, before he's been told of the outcome of his surgery, Jennings celebrates its success, and resolves to Live Every Day Like It's His Last—this surgery was his “call to arms.” After being slightly perturbed at the idea that he has received a black man's heart, he regains his optimism and is shocked when he hears that no heart was found. Thus ensues a bit of Monty Python style gabbing that results in our discovery that a bomb was found instead of his heart, and that the bomb was left in. Again, the unreality of the scene is played unapologetically. Jennings has had his ribcage spread open recently, and yet bears no apparent physical after effects.

At this point, it's worthwhile to again consider the wealth of choices that Cederquist had at his disposal when crafting the atmosphere of the play. In a small venue, the threat of physical violence (as demonstrated richly by R & D Violence design in their work in the recent production of Extremities) can be very, very upsetting. The threat of imminent explosion from nails and ball-bearings could be unbearable. Walker and Cederquist conspire to create an atmosphere that makes this subject palatable.

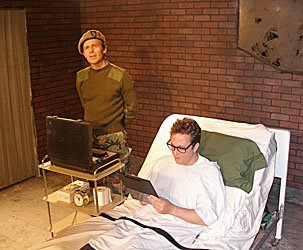

Then the parallels to the GWOT are presented. Jennings is confronted by a simpleton MI-5 agent named Psmith (played by Brian Parry and pronounced “Smith”), who electrocutes him to get him talking. The Gitmo parallels start flowing. “It's not torture,” says Psmith, in the reletivistic jargon of the Bush administration, “it's medication.” The portrayal of Jennnings' electrocution is so unreal that it almost becomes funny.

Psmith is the operative whose work isn't publicized or explained. The coerced confession, Jennings righteous demand for his rights, the promise that “we'll open up everyone we have to [to discover more bomb-implanters]” all follow. Psmith jusitifies his actions in times of war, and squeezes a confession about a Muslim client of Jennings' being a terrorist. Act I closes to Psmith's threat against Jennings' family (and the showing of an home video shown on an on-stage TV). Jennings is bathed in a lonely green light as he calls for his wife's help.

Act II opens to the same lilting music and the entrance of a Colonel (Dan McNamara), the Good Cop. He frees Jennings' bindings and gives him water. He takes testimony from Jennings about his treatment up to that point, and expresses his dismay at it, offering an apology, and assuring Jennings that the account of his treatment will make its way into a government report. We can safely assume that this will be another Abu Graib bureaucratic report that has relatively little political or other consequence. The Colonel cites Jennings' mistreatment as the result of a “bad apple.” For the Colonel, Jennings' mistreatment is a cool rhetorical subject. We later learn that Jennings wrote an indignant letter to the Times of London on the subject of human rights issues in the GWOT. Until recently, Jennings approached the subject of human rights violations just as we do (and as the Colonel does)—blithely and as a hypothetical question.

The Colonel is a slick creation, as the warrior with a “conscience.” He may be acting on hysterical impulses, but where Psmith is excitable, the Colonel calmly assimilates innocuous facts into worst-case scenarios. He is the satirized public face of the excesses and stupidity of the GWOT. He wants a confession to track down the other members of Jennings' cell. Rather than torture him, he blackmails Jennings with photos taken of him in a comprimising position with the slutty nurse as he was unconscious prior to his surgery. (Another Abu Graib style humiliation). Jennings agrees to sign a confession.

Why are Jennings' captors acting this way? Clearly, if Jennings purposely had a bomb implanted, there is no reason for him to have voluntarily walked into a government clinic for open-heart surgery. None of the government agents consider this. We later learn that Jennings had been tracked by the government ever since his letter to the Times. The slutty nurse was of course a government agent, as was the doctor. Was this a government plot to frame an ordinary white liberal as a terrorist to justify further intrusions on civil liberties? Was this a plot by the doctor to frame Jennings, whose wife he absconds with at the end of the play?

The bigger picture is never really elucidated. The authorities' actions are senseless. We learn that the room in which Jennings is lying is girded by thick concrete, and he will be allowed to explode there. We endure a projected explosion deadline that passes calmly. We begin to wonder if there really is a bomb, or if something else is happening. Jennings' wife (Lauren N. Goode) enters and confronts him with her abandonment and the prospect of his childrens' placement in foster housing (as his wife starts a new life with the doctor), completing his utter ruin. Another deadline is announced, for which Cederquist builds suspense with the proverbial ticking time bomb sounds. (The rhetorical justification for torture typically involves the phrase “Ticking Time Bomb”). Jennings responds to the prospect of his imminent explosion in a defiant, beautiful speech in which he implores the audience to “stop the madness.” When death doesn't come precisely at the moment that it was predicted, he celebrates. And then his celebration is cut short with the sound of the explosion.

In the world of this play, is the threat of mass destruction through terrorism real? We don't ever really understand why Jennings has a bomb inside him, but the fact is that there WAS a bomb inside him. There WAS a threat, and, unless the bomb was implanted to frame Jennings (which it may well have been), lives were saved by his having exploded underground.

In this play the threat is mysterious. The only thing that is clear is the government's ineffectiveness and absurd cruelty in actually understanding and uprooting it—that is, unless they created it in the first place. I feel that the play would have been a more effective treatment of the GWOT if it were clear that there weren't some nefarious government scheme by which the bomb was implanted in Jennings—but that's because I'm not given to conspiracy thories. If the bomb were presented as a real parallel to how I perceive the threat, then I believe that this play would have a much darker varnish. We're in danger, and, while we may be occasionally saved from well-publicised attack plots, the government really is too stupid and cruel to solve the problem in any meaningful way.

Damien Arnold's work in this piece is excellent. He changes rhythm and tone in connection with Cederquist's lightening and darkening of the mood with sincerity and pathos. The rest of the cast is appropriately in rhythm with pace of the storytelling throughout (including Julia Siple in a thrilling voice-over cameo). Cederquist's staging, and the designs of Sean McIntosh (sets), Jon Kohn III (lights), and Jennifer M. Hawk (costumes) are all appropriately scaled down and simple for the tiny black box at Actors Workshop. I wonder if the play would be more appropriately staged in a larger venue, and more elaborately, to allow the ensemble and designers to create a running commentary on the material without worrying about rendering the tone of the subject too “real” for the audience to maintain analytical perspective. In any case, Cederquist and Walker have conspired to offer the first history of the GWOT that I've seen in a theater in Chicago, the beginning of a necessary conversation on the subject between artists and the culture.

6 comments:

top [url=http://www.c-online-casino.co.uk/]uk casinos[/url] hinder the latest [url=http://www.casinolasvegass.com/]casino bonus[/url] free no deposit perk at the best [url=http://www.baywatchcasino.com/]easy casino

[/url].

We are a group of volunteers and starting a new scheme in our community.

Your site provided us with valuable information to work on.

You have done an impressive job and our entire community will be thankful

to you.

Feel free to surf to my web site: helpful resource

Normally I don't learn article on blogs, but I wish to say that this write-up very pressured me to take a look at and do so! Your writing taste has been surprised me. Thanks, quite great post.

Have a look at my web page - free pyschic reading

My page - psychic eye

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an extremely long comment but

after I clicked submit my comment didn't appear. Grrrr... well I'm not writing all that over again.

Anyway, just wanted to say great blog!

my website: click here to visit them

I've learn a few excellent stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much effort you set to make any such fantastic informative site.

Here is my webpage fast payday loan

please read the following post.

TRAVERSE SURVEYING Chain Survey Prestressed Concrete Reinforced Concrete Use of Pushover Analysis Results KINEMATICS OF FLUID FLOW Pushover Analysis

Post a Comment